Many fencers have experienced, either personally or in a teammate, the devastating effects that an injury can have on training. While traumatic injuries are less common, the inherent asymmetry of the sport, repetitive movements required for many techniques, and sometimes awkward positions required for those same techniques, make fencers more prone to certain types of overuse injuries.

This article will describe a few of the most common yet avoidable injuries, possible treatments/alleviating factors, and how to avoid them in the first place. This article is intended purely as a source of information and education. Any injury should be specifically examined by a physician or physical therapist on a case by case basis, and this article should not be considered in any way a replacement for seeing a health care professional.

Fencer’s Elbow

I will first describe the common “fencer’s elbow”. This overuse injury is very similar to tennis elbow, with likely slight differences in anatomical origin. This injury tends to be somewhat more common in foil fencers. This is likely because foil tends to be the weapon in which the wrist is the most mobile and used repetitively , particularly when the flick was still the most effective way to score. Why, one might ask, am I discussing the wrist in a section meant to be discussing an injury involving the “elbow”?

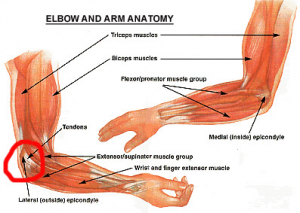

The muscles that control wrist motion all originate on either the medial (closest to the body) or lateral (towards the outside of the body) bony ends of the upper arm. The muscles that control wrist flexion (curling fingers and wrist towards the body) originate on the medial side, and conversely wrist extension (spreading fingers and wrist away) originate on the lateral side (red circle). Lateral epicondylitis, the more technical term for “tennis elbow”, is quite literally an inflammation of the origin of the muscles that control wrist extension.

The wrist extensors are more prone to overuse injury for a simple reason: our grip is strongest when the wrist is not neutral, but rather slightly extended. You can test this simply by trying to grip something as hard as you can, and observing the position your wrist tends towards naturally.

In fencing, people often make the mistake of gripping their weapon too tightly. Particularly in foil, fencers tend to use many repetitive motions of the wrist to take the blade and flick. This is different from epee, for instance, in which flicks are less common and the arm tends to move more as a whole unit, in a smaller range of motion.

This overuse can be very taxing on the extensor muscles, and can, lead to chronic inflammation of the area where they originate. This leads to pain when gripping, moving the wrist forcefully, and generally almost any of the motions required to manipulate a fencing weapon.

Patellar Tendinitis

The next condition I will tackle is commonly called patellar tendinitis. I will also discuss an separate type of knee pain called patellofemoral pain syndrome. Patellar tendinitis is a pathologic condition that involved inflammation of the patellar tendon:

This tendon of course, is activated whenever the quadriceps muscles fire, which are extremely important both for maintaining the “en guarde” position, and for initiating and recovering from almost all footwork movements.

The deeper the en guarde, the greater the amount of stress put on this tendon, and the harder it has to work. If a fencer over trains or does too many conditioning exercises in a very deep en guarde or squat position, especially with the knee positioned forwards over the foot (instead of the ankle), they will be prone to overworking this tendon, and it may become inflamed.

This condition can make almost any footwork extremely painful, and may keep a fencer from maintaining proper form.

Patellofemoral pain syndrome is generally caused by a muscular imbalance which causes the kneecap to track improperly, or to grind into the knee joint. A common culprit for this maltracking is the TFL (tensor fascia latae), which is attached to the infamous IT (Iliotibial) band:

Treatments for these injuries:

There are some common treatments that can work to alleviate symptoms from all of these injuries. The first and simplest solution is generally at least a short period of rest.

Logically, an overuse injury can be made less severe and assisted in healing through decreased use. However, most athletes are unable or unwilling to take a rest period, particularly in the middle of the fencing season. While this is understandable, I would advise that the benefits to be gained from helping an overuse injury heal greatly outweigh the supposed loss from missing a short period of training.

There are other general treatments, however.

Icing after an intense practice or training session is an often underestimated way to alleviate symptoms. Ice will not only decrease pain, it will also stop irritated areas from swelling and becoming even more irritated. Icing should generally be done for anywhere from 10-20 minutes, and never with the cold surface in direct contact with skin. Ice should not be considered a permanent solution by any means. But it can assist in making an injury more manageable.

For fencer’s/tennis elbow, ultrasound is often used. While this has not been proven outright to help in all circumstances, it certainly can assist in tissue healing and improving blood flow and tissue metabolism. Strengthening of the forearm and hand can help ensure that the muscles can cope with amount of stress being placed on them while fencing. Appropriate strengthening exercises, as well as volume, should be prescribed by an expert health professional.

For patellar tendinitis, some athletes do get relief from a small supportive band placed directly below the kneecap. While these have not been proven to affect the mechanics of the joint, if they decrease symptoms then they can be worn.

Knee strengthening supervised by a physical therapist is the best long term solution for this injury, however, and may require some time. Rest is still the best treatment, and care should be taken to prevent the injury from happening in the first place.

Patellofemoral syndrome treatment should also be supervised by a physical therapist, as it can have multiple causes. However, taking care that the alignment of the knee is straight while conditioning and fencing can ensure that the kneecap does not get pulled up or to either side over time.

If a fencer tends to rotate their knee inwards while fencing, rolling and/or stretching the IT band might be a good start to fixing the problem. Just as in other injuries, appropriate and supervised strengthening can go a long way in helping the involved area cope with the stresses placed on it during sport activities.

Preventing Injuries

The best treatment for all of these injuries, of course, is prevention. For tennis elbow, this should start with a careful examination of technique. Gripping the weapon too hard, particularly at an extreme angle of wrist extension, makes one more prone to irritation. The grip should be examined to make sure that all fingers are appropriately supported. Finally, particularly when taking a six parry, care should be taken not to make extraneous repetitive motions, as fencers often do.

The number of rapid alternating movements of the wrist should be curtailed as much as possible to avoid irritation. Great care should be taken when switching grips, and activity with the new grip should be ramped up slowly. Some grips put a particular stress on one finger, or encourage particular movements at the hand and wrist. If a fencer’s muscles are not accustomed to these stresses, they can easily become irritated.

As for the legs, one of the most common mistakes in conditioning young fencers is doing repetitive bouncing exercises at the end range of squats. This is particularly a bad idea in young fencers, who are less likely to have the strength (particularly due to their continued growth) to handle this type of exercise. Great care should also be taken to examine a fencer’s footwork to ensure proper alignment (as stated above).

Plyometric exercises should not be initiated until the fencer had a good stable base of strength to work off of, and should be constantly supervised to ensure that he/she lands in proper alignment and with good control.

Finally, treatment of any injury is easier if it is caught early. Younger athletes should be taught the difference between muscle soreness and an actual irritation, and should be encouraged to speak up if they are in pain.

Athletes often try to “tough it out”, and in many of these cases end up having a much longer rehab process later on. This is as much the responsibility of the coach as it is the athlete’s. If the coach feels that they are not skilled enough to supervise strengthening appropriately or notices that many of their students are getting injured, they should seek the help of a professional. Coaches and parents should always watch for warning signs (limping, complaints of pain, etc.), and any pain or injury should be dealt with as soon as possible to increase the chances of a successful recovery.

Resources

To find a PT in your area: www.apta.org (go to “find a pt” at top of page)

For general info: www.mayoclinic.com, http://orthopedics.about.com

References

- Dutton, M. (2008). Orthopaedic examination, evaluation, and intervention. McGraw-Hill.