{mosimage}

March 2004. In March 2004, St. Petersburg, Russia, hosted a Grand Prix World Cup for foil. With the Olympics fast approaching, this tournament was a chance for fencers to qualify, or at least finish the season strong. The overall fencing talent represented hundreds of world cup placements, and the "last-train-to-Athens" feel generated enough performance pressure that a deep-sea fish would implode in a succulent red mist.

You can purchase the DVD of the St. Petersburg 2004 World Cup at the Fencing.Net Store

Perhaps because of this, the finals were dominated by fencers who already knew where they would be on August 2004. Cassara, Gruchala, Guyart, Mohammed and Trillini, these athletes show up in World Cup finals again and again. No World Cup tournament would be complete without them. (The normally omnipotent Vezzali sat this one out in 9th place; her line on the results list positively vibrates with unanswered questions.)

But new names emerged in St. Peterburg. Slawomir Mocek of Poland was present as a very strong and interesting fencer. In Golubitsky’s newest DVD, he was a featured opponent in the 2001 Venice World Cup semi-final, however he’s been fencing for a while — second in the 1999 European Championships, third in 2002. In the 2000 Olympics, he was knocked out (by Germany’s Richard Breutner) just before the quarter-finals. He’s good enough to place, and experienced enough to be dangerous.

Serguei Tikhonov (or Sergey Tihonov, Russian names are never spelled the same twice) was a positively new face. To enter the semi-finals he beat Russia’s foil Pozd, Viatcheslav Pozdniakov. Tikhonov was 59th in Vienna (Dec 2003), 51st in Seoul (Feb 2004), and 29th in Bonn (May 2004), so he’s stronger than most club fencers and getting better — but he’s still not a first pick for world domination (36th in points). He was fencing above himself in this tournament, with the St. Petersburg audience wildly cheered his every touch, him being the only Russian in the finals.

Also making an appearance in was Margherita Granbassi, the secret third Italian women’s foilist, 9th in World point standings. She was 24 years old in March 2004, and she has a very promising career should she ever get out from under Vezzali’s and Trillini’s shadow.

Next: Men’s Foil

{mospagebreak}Men’s Foil

Slawomir Mocek (POL) vs Brice Guyart (FRA)

Mocek’s fencing is close to the baseline standard: not short, not tall, not flicky, not tippy. He is well-rounded. Hooking up against a curiously restrained Guyart, he rapidly gives himself a 4-1 lead with long attacks and fast bladework, usually on the French side of the strip.

Guyart, in the early bout, is stiff and tightly bundled. His blade actions are crisp and his footwork is a model of precision, but he pulls his attacks when he needs distance, and undercommits when Mocek is open. As if embarrassed at being so tall, Guyart seems unwilling to showboat his tremendous reach and killer fleche, and he burns a lot of energy merely by holding himself back. At times he’s fencing both the opponent and himself. This is tremendously tiring, and he is at the end of a long tournament. A more relaxed Guyart would have been better situated for the next bout — Mocek turned out to be his warm-up for Cassara.

When Guyart finally "lets go," it’s with running attacks and ripostes. Guyart knows he can sustain long, multi-action phrases, so he starts prolonging the action in order to force a favorable conclusion. He tenaciously refuses to let Mocek get away before a light is turned on. Closing to 5-4 Mocek, Guyart attacks, is parried, counter-parries and — finding his opponent fleeing — ripostes at a run… he is counter-counter parried by Mocek, and then counter-counter-counter parries with a riposte flick to the back.

More than once, Guyart runs in the middle of an action — true confidence. But Mocek’s marches are even more daring. With the video on 1/4 speed slow-motion, you can see Mocek comfortably stepping forward, while Guyart’s repeated stop-hits vibrate 3 inches short of his chest. Here is a fencer who knows Decision Point. Mocek has no problem dealing with the Frenchman’s reach and the numerous cobra-fast counter-time threats that Guyart can throw out during a full-strip retreat.

|

Nor is Guyart immune to being tied up in Mocek’s blade, even if Guyart can make a counter-counter-counter parry. Mocek’s blade keeps Guyart sufficiently uncomfortable so that he keeps pulling his attacks. Guyart’s killer fleche doesn’t appear until 12-9 Mocek.

The most glorious touches are flicks over the shoulder, but those are few and they always appear as a last resort. Also impressive are some radical close-outs from Guyart into Mocek’s preparations. Most of the points are scored conventionally with the point.

In the end, it’s Guyart’s pulled-hand attack which clinches the bout. Coming to terms with his height and reach, he begins to use a tall-people move: He attacks, pulls the hand so Mocek’s parry doesn’t connect, then extends from the hip to land on some extreme edge of Mocek’s lamé. He’s sufficiently long and fast enough that this does not cause him undue risk. During the final extensions of those attacks, the tip easily travels six feet or more. This is the fencing Guyart seemed to be resisting in the early bout. The moves are so comfortable and effective they might be licks from his junior days, which he’s trying to leave behind but can’t quite do without.

Sergui Tikhonov (RUS) vs Andrea Cassara (ITA)

Meanwhile, Italy’s young cowboy, Andrea Cassara, takes on Sergeui Tikhonov of Russia. Cassara is big; hitting him would be about as challenging as punching a wall, except this wall punches back. Even while his long, relaxed gait crosses the strip, his arm is sweeping from the elbow in a disjoined tempo. Opponents can’t look at his distance and say, “Ah! It’s clear what I must do.” He is complicated. Cassara’s target looks easy to reach, but his hand is devastating. The information he conveys on strip is conflicting, which eventually paralyzes his opponents.

Tikhonov, unfortunately, also keeps a deep, elastic guard position. He is the sort of fencer who sits lower and lower when he gets excited. He needs an upset to get past Cassara, who is turning into one of the most unbeatable foilists of the decade. So, excited, Tikhonov sits lower and lower — and Cassara barely has to reach to flick his back.

|

Towering over his opponents with his natural height and a shallow en garde, Cassara ignores front-facing target and executes 80’s-style flicks to the deep back. (Tikhonov arches back in pain when Cassara nails his tailbone.) He is too big to match the tempo intricacies of his team-mates Sanzo and Vanni, and the most effective tool in his belt is a wall-of-threat, strip-crossing march. Thus, Cassara is most interesting because of what and how he will suffer under the timing-changes. What he enjoys about fencing may be stripped, or reduced, and he’ll be left playing his (considerable) length to block-time opponents.

There are promising-looking holes in Cassara’s fencing. He brings a lot to the director: He couldn’t live without rule t.56.a.2. His footwork is penetrable (easily penetrable, if you’re one of his team-mates fencing him in a final). Cassara is a sportscar hand on an SUV body… and what’s more, he’s not really ready to be on his own. He receives, and seems to need, move-by-move counsel from his off-strip coach. Based his simple joy in screaming after a flick, he seems ripe for psychological warfare, as if he might falter if he weren’t able to make an affirmation-scream for half a period.

Tikhonov is not the best fencer to exploit all these tantalizing holes, but he works bravely and finds some unlikely solutions. He frustrates Cassara’s flicks by closing distance with a high prime, his hand so high the tip seems to score on Cassara’s collar bone. During a strong run, 10-9 Tikhonov, he discovers that all you need to hit Cassara is to attack, to warp through the Italian’s sweeping blade and hit the target behind it. But then he forgets.

|

The bout looks like another Cassara drubbing, but in fact Tikhonov brings the score to 14-14, fencing with nothing but a lot of gusto, a very strong middle-game, and an enthusiastic audience. Tikhonov finishes his night 50 places above his usual.

So which is it? Do the top elite fencers place so consistently in the world cups because they are head-and-shoulders above the rest of the fencers? Or are the competitive margins so thin that an elite fencer can nearly be upset by a lower-50s fencer?

The apparent answer is that the margins are thin, and any fencer has a fair chance of placing. Or, perhaps, any fencer can tank to a lesser one in the eliminations — Guyart can be 34th one competition (Aqaba), and 1st the next (Paris). In this tournament, scores of 15-14 were the rule in the quarter- and semi-finals, for both men and women.

The consistently top-placing fencers don’t have a vast edge in skill or technique. Instead, their edge is purely mental: Tournament after tournament, they score one more point than their opponents. Once is a fluke, twice or more is a message.

Brice Guyart (FRA) vs Andrea Cassara (ITA)

In the quarter and semi-finals, every men’s bout was 15-14 (excepting Slawomir Mocek’s 15-13 win against Italy’s Marco Vannini).

Gold medal matches, however, have their own logic. The fencers unshoulder their day-long strategies. They relax their long-range competitive mindsets. All the prior encounters are mere lead-ups to the final, real match, which is where two competitors can finally maximize their fencing without any care for the future. The last bout is the tournament. So the St. Petersburg Foil Grand Prix is about how Guyart got smoked by Cassara, and how Guyart got mad and took it out on Cassara’s team at the Olympics.

Guyart is tall (6’1″), but Cassara is taller by three inches, and has forty extra pounds of weight to generate more fright in his opponents. At 2-0 Cassara, Guyart has learned to fear (but never negate) Cassara’s flick. Tikhonov felt severe back-pain during his bout against Cassara, and when Guyart doubles out, he, too, is left clenching his back in agony after a heavy flick. Meanwhile, Cassara gives a jolly bellow, “Yo yo yo!” as he happily lopes back to the guard line for the next attack. His off-screen coach confirms: “Molto benne!“

|

At 6-0 Cassara, the spectator starts to grow angry: When, oh when, will France learn how to confront a marching attack? 2003 World Cup: France’s Sebastien Coutant was destroyed with a very unflattering score by Cassara’s march. 2002 World Championships: Team France obliterated by marching Germans. The French answer to the march is to huddle down, and hope the opponent is aiming for someone else. It’s not as effective as they seem to believe.

|

But this is Brice Guyart, he will have a fix for his middle and end-game, which is when he really takes off. Cassara is a tremendous fencer, but he’s not 6-0 material versus Guyart. Guyart is just a slow starter. So what will his solution be — to stretch further? To unleash his devastating fleche? 45 seconds into the first period, Guyart finds his end-game: The hand-on-hip attack. It somehow fails to elicit Cassara’s devastating stop-hit. Then Guyart lands a parry, delayed-riposte (hand from the hip again), which is somehow unanswered by Cassara’s usually prescient remise. Then, finally the Guyart fleche, which should have shown even the most obstinately blind fencer the way to win. Guyart narrows to 5-8 with yet another attack.

But the rally ends when Cassara unleashes his own attack, a lanky march finished iwth a deliberate flick to the back: Here’s what I have. Guyart may have been too tired to find inspiration — his Mocek bout was more energy-draining than Cassara’s Tikhonov bout, as Guyart was fencing tight as a drum, and Cassara in comparison seemed fresh from the masseur‘s table. Cassara may also merely be a bad fencer for Guyart: Guyart starts slow, and Cassara can’t be stopped once he scents victory.

|

In a few months at the New York World Cup, Guyart will eviscerate Cassara’s team-mate, Salvatore Sanzo, predominantly with the fleche. And then he’ll beat Sanzo again at the Athens Olympic Games, after squeezing past Cassara 15-14. Guyart starts slow, but then he picks up speed.

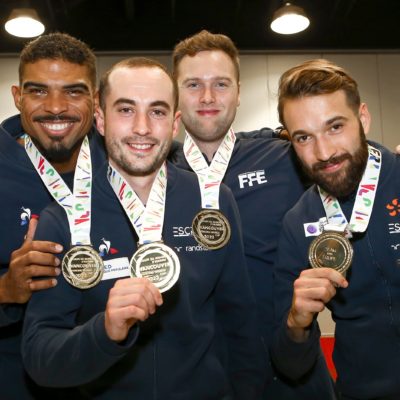

| {mosimage} The men’s award ceremony, complete with traditional mu-mus. |

Next: Women’s Foil

{mospagebreak}

| {mosimage} Italy’s Valentina Vezzali, |

Women’s Foil

Gargherita Granbassi (ITA) vs Giovanna Trillini (ITA)

The Italian women are immensely successful, but the fencing isn’t always bella.

The Italian women’s movement is pared down, not efficient so much as it is excised. The footwork falls into some narrowly defined system or it’s simply not used. In the same way, climbers going up Mount Everest have their toes amputated, so they can’t get frostbite. The bladework is stiff and formal (at the start), as if their trainers whip them if they show any improvisation. Early in the bout, Granbassi makes a high remise around the head — but stops herself, as if remembering there is a punishment for flair.

When Granbassi and Trillini get on guard, the initial styling makes the most sense if you imagine their blades were 45 inches long, and heavy. The hand is cocked up, tip pointed at the ceiling as if to support the weight of an immense weapon, and on-blade actions are made with great caution. Attacks conclude far short of target — at times, the fencers launch three or four alternating lunges that barely reach their opponent’s bell guard, as if they were expecting 10 more inches of reach from their blades.

| {mosimage} Granbassi watches her team warm up at the Olympics. Note the developed fencing tan. |

But these are just first impressions. Inevitably, at some point during the bout, the fencing turns fluid and very logical. However it’s not the fencing that changes — the viewer’s mind suddenly wraps itself around all the strengths being displayed. The awesome timing, the syncopated footwork which is designed to generally succeed. The Italian attack is a shortened lunge, actually quite vicious looking (that’s a good thing). The hand is slightly delayed, and is usually aimed to hit near the high inside line. They rely on this short lunge against all fencers, and it works very well when they find the tempo.

There is also some evidence of the Vezzali footwork patterning in these two women. The earliest available video of this repeating footwork technique (step forward, alternate feet, step back, alternate feet, and repeat — but everybody has their own pattern) has Valentina Vezzali using it to great effect on Sylwie Gruchala in the 2003 World Championships. Italian bulletin board member Cavatione reports that the footwork is indeed highly trained, a version of the Italian approach scherma da terreno, or ground fencing: "continuous movements back and forth with sudden attacks on the step or in a "passata."

The key concept to the Italian women’s approach is restraint, and their restraint reflects an unholy self-control and an utter belief in competitive psychology. There is no risk-taking: It’s a duel. You run the numbers and you win. This has been perfected by their team-mate Vezzali, Athens gold winner and winner of more than 50 World Cup medals, but it’s not as strong in Granbassi and Trillini.

|

Granbassi fights pugnaciously but never achieves a double-digit score, and she accepts her loss seemingly without surprise. Born in 1979, she is luckier than some of her older peers. She will be eclipsed by Vezzali and Trillini for only the beginning of her career, since one or both of her brilliant older teammates are expected to retire soon. Meanwhile she’s placing well, and polishing her game against the other notables.

Sylwie Gruchala (POL) vs Aida Mohammed (HUN)

{mosimage}

The next bout pits the ever-present Gruchala against the ever-present Mohammed. The Google doesn’t exist which can answer how many times these two have faced off in the semi-finals. Mohammed is the underdog here. Always close, never the breakout, and continually edged out by Gruchala whenever it seems to count the most.

Mohammed has impeccable footwork, and can generate great speed and power. Playing a very smart game, she uses her distance at the beginning of the bout to rob Gruchala of her long attacks. She keeps far in front of the tip and waits with iron reserve until Gruchala reveals her destination target. She then snaps up the parry riposte before Gruchala can bring her hand around. She gains an early lead by being defensive, which causes Gruchala to hesitate and second-guess herself. When Gruchala hesitates long enough, Mohammed takes the attack.

Gruchala has better luck defending against Mohammed. She reflexively counter-attacks any forward preparation (it doesn’t matter who she’s fencing), and she is fluid and long enough to land a touch around any obstruction. Her odd hand makes for unpredictable targeting, as she can angulate anywhere. Having drawn Mohammed out of her defensive mood, she again launches her long attack. She knows she must use them now, because they may not work against Italy.

Gruchala-Mohammed — Mohammed’s (right) early-game strategy to close down Gruchala’s long preparations: Wait, and take the openings, and kill Gruchala’s confidence… and meanwhile, run away from Gruchala’s long attack. |

Gruchala is immediately recognizable on strip, based on her preparations, her advance-advance-pittypat footwork, and her hand. In other tournament videos, the audience can be heard commenting on the epic weirdness of Gruchala’s hand.

Gruchala keeps her wrist in a bent-back, “broken” position, like she’s pushing open a door. It would be a high three position, except that she keeps it in the middle of her body below the sternum. Coaches may groan at the hand, and sports-injury therapists may mentally tally bills, but it works for her, because it’s a specific tool for attacking. Fencing her, you might want to feint to her six — she would have to move her whole arm to parry — but as you start your feint she’s hit you and is walking back to the guard line.

Fencers certainly don’t want to be on the receiving end of Gruchala’s long attack. The Italians, through long exposure, have made an art form of not letting it begin. On the attack, Gruchala steps forward, bell at her lips like she’s saluting, wrist abominably broken. When the opponent gives ground, she follows them, shaking the blade invitingly. When the opponent finally gives her something to work with, she makes a careful placement to the high target, or the flank when she’s really reaching, and she’s not above flicking to the back. Her lunge is tremendously long, but she rarely needs all of it after chasing down an opponent. Most opponents have learned that the best percentage is to attack on the preparation. Opponents who flee can get hit from twelve feet away.

But with that hand, Gruchala only gets points because she really, really wants them. It’s not useful for improvisation in the middle of an action, and there certainly cannot be an emergency that requires a quick hand fix. She cannot make an error, and coast through on technique. She won’t score unless she’s killing herself to turn a light on with an attack or counter-attack. This is not the weakness it would seem to be, because Gruchala’s willpower is unswerving and her focus is only ever shaken by fatigue in the end-bout. Gruchala is a frequent winner, but she always fences like she’s down 10-0 in her first DE.

| {mosimage} Sylwie Gruchala ponders her extreme lunge. |

The third period begins at 9-9, and both fencers having trouble finding target. Gruchala’s ripostes go off target (due to the wrist), and her attacks land only occasionally. But as she edges towards the win, it’s clear she has more than luck going for her. Gruchala is a hard worker who spends a lot of time engineering each hit. And every so often, she surprises everybody with some unimaginable ornament — a tiny disengage, a beautiful transfer to flank, a windmill riposte.

Giovanna Trillini (ITA) vs. Sylwie Gruchala (POL)

Gruchala and Trillini face off in the finals. The fencers are cautious and exploratory. Vezzali often knocks one or the other out, and they may not be as familiar with each other as they could be.

Gruchala graciously allows Trillini to walk onto her point a few times before the bout really heats up. The pretty touches in the early game come from Poland, including a tremendous tempo attack that leaves Trillini swishing the air. Both fencers move quickly and easily, but their tips are too high, and their legs are too powerful. They have trouble bringing the tip to bear on target in time. Their distance is so important that the handwork suffers.

|

However, it’s handwork that plays the decisive role in the bout. Where Mohammed pitted her distance against Gruchala’s distance, Trillini pits her hand against Gruchala’s hand. Gruchala’s handwork is an open invitation. It might well be her only exploitable weakness. Trillini shelves her minimalist approach, and engages in longer actions with back and forth, quickly bringing Gruchala to the edge of her abilities. Gruchala likes to take risks even when she’s leading. She fences with a desperate pliability in her whole frame, sacrificing form, balance, and technique to get the touch, but this doesn’t help her bladework. Trillini narrows to 4-5 with a nice riposte after Gruchala spends one whole phrase balanced on her front leg.

|

If Trillini stays calm enough, she knows Gruchala will eventually reveal enough flaws and lose the bout. But Trillini gets easily embroiled in the actions, and at 7-7 when Gruchala starts to pull out her long attacks, Trillini bites at every feint. Both fencers work their strong game, trading between strong Gruchala attacks and Trillini bladework. Bladework trumps footwork in Right of Way, which Gruchala doesn’t like. After one action, she holds up two fingers — by her count, it’s twice the director has robbed her.

Trillini methodically recovers from her slow start, and soon Gruchala is the underdog for real. As Trillini polishes her successful strategy, she generates longer and longer phrases until the Polish fencer’s hand can’t keep up. By the time the critical action of a phrase rolls around, Trillini’s light is on and Gruchala’s tip is out in space. At 14-11 Trillini, the Italian knows she just has to wait… and there it is: Gruchala attacks, Trillini parry ripostes, and then remises through Gruchala’s weak-wristed counter-parry. When everything else is equal, the hand is what wins.

|