{mosimage}Most fencers, at one time or another, have been terrorized by a marching attack. These attacks are compound, so their destination target is hidden until the very end. They are also methodical, so they are difficult to break apart. The attacker scores, and issues an alpha-male/female howl. The defender is left reeling, feeling singularly inept and confused about what they should have done to stop the atrocity.

Textbook marching attack:

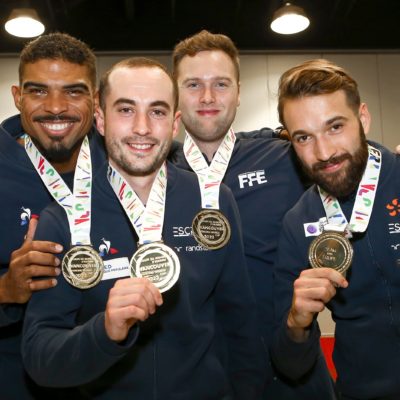

(From “Foil Fencing Actions CD-ROM,” now on Fencing.net!) |

Many touches in foil fencing are the result of a surprise — some quick, fast, simple attack which the opponent didn’t see coming. All the other touches in foil fencing are ones where the opponent did see it coming, but couldn’t do anything about it. Marching attacks fall under the latter category. Long compound attacks, they don’t score with sudden tempo changes or clever bladework, but by metering out ever-increasing threat which eventually causes the defender to crumble. |

Marching attacks are anywhere from two to two million actions long. They are not surprising in themselves (surprise attacks are more direct and simple). They function by drawing the opponent’s attention from one feint to another, until the opponent’s hand is sufficiently out of line to allow a touch. The opponent’s controlled retreats become full flight as the attacker steadily applies pressure. This pressure comes in the form of compressed distance, absence of blade that causes the defender to search, and mounting speed that causes the defender to fly backwards, ever more off balance. Some of the most gratifying — and definitive — touches in foil are the result of a good march that causes the opponent to fall apart.

Is a “march” a real term? Martini’s Fencing A-Z doesn’t contain an entry for “march,” but it does define trompements as the feints and disengages made during a march. In video of the 1989 World Championships, the directors used attaque a la marche seemingly as a synonym for attack on preparation. Sergei Golubitsky, called the march a promenade in his recent interview. It’s also been called a chase and a charge. Whatever you call it, it’s a very useful sort of attack, one which is here to stay regardless of any pending FIE foil changes or varying interpretations of the rules.

Marches are long compound attacks, and the “marching” comes in because of their multi-step nature. The feet have to do something while the hand is perplexing the opponent, and they are usually put to making combinations of short advances, appels and jumps, all with broken rhythm to resist tempo-based attacks on the march. While the feet are making these confusing tempo changes, and generating lots of confusing noise (shuffling and tapping), the hand is further complicating the opponent’s life by feinting to different target areas and executing trompements.

The most destructive thing about the march is its longevity. They can wear down even the most rabid parry-er, they can inflame even the most phlegmatic old-timer. Caffine won’t help, and neither will zen. The defender flees from the march until they’re out of strip, or they give up and root to the ground.

The end result of a marching attack is an attacking fencer with a lot of momentum, who delivers a flying lunge or a fleche against a defender who is thoroughly scattered. The defenders all have the same pose as the machine buzzes — legs straight, body leaning wildly, hand making a parry out in space.

When to use

Simple attacks versus marching attacks: Simple attacks hit the opponent because of surprise. Marching attacks hit the opponent when there’s no surprise. Simple attacks are about not allowing the opponent a chance to react. Marching attacks are about getting the opponent to make the wrong reaction. Opponents shouldn’t see short and simple attacks coming. Opponents should see marches coming. Simple attacks threaten target. Marching attacks imply threats to target, until the actual attack is delivered. |

Early in each bout, your task is to find your level relative to your opponent, so you can use the correct kind of attack. Begin with simple direct attacks — if you’re winning with these, you never need to change. If you need more, go to short compound attacks. If you need still more, go to simple direct attacks with second intention. If you need even more, go to compound attacks with second intention. If the opponent can handle all these attacks with flair, remaining balanced and poised, then your opponent (relative to you) is skilled, has good distance, and is probably fresh. This is a candidate for a marching attack.

Each type of attack carries with it increasing levels of risk. As you “escalate” through the attack styles, you’re running an ever-greater risk of making an error and getting hit. Using a too-sophisticated attack against a low-level fencer will only bring you to grief. For example, don’t try second-intention against a rank beginner — they won’t react usefully. Don’t try compound attacks against a fencer who can’t see a feint — they’ll just lunge at you.

In the same sense, you don’t need to march if (1) your opponent can be surprised, (2) their reactions are slow, (3) they can’t see an attack coming, or (4) they don’t understand when they’re in danger. Rule of Thumb: Only use marches against fencers who are as good or better than you, and nothing else is working.

A march is a house of cards

Marches are constructed carefully, with the hand and feet trading off between offense and defense. While the hand is threatening, the feet are keeping safe distance. While the hand is resetting, the feet are generating protected footwork that can be used to grandfather an advance lunge into the action. This all makes marches hard to break apart, and the defender is obliged to cede ground while looking for a counter-tactic. The march gets faster near completion, as (hopefully) the defender is “opened up” and susceptible to a hit. |

The march is a combination of footwork and handwork. Foot and hand work together to make the march stable and difficult to stop.

The director says, “Fence!” and the fencer makes a few ominous moves forward. The opponent indulges the fencer, and gives a little ground. The fencer takes up the slack, faster, and the opponent gives more ground, faster. If everything is going well for the fencer, their opponent is entering a defensive mindset, moving backward and searching for the blade.

This all works because the rules protect the attacking fencer’s final advance lunge/fleche provided the hand is extending and the tip is threatening target (t.56.a.2, t.56.a.3). The marching fencer must constantly keep their arm extending, just in case their next step is their last one before the finish. If they don’t keep their arm constantly extending, they must withdraw the hand at a time when they know the opponent won’t be able to take over the attack, and then start the hand extending again. A bent arm can be counter-attacked, but in itself it doesn’t deprive the marching attack of its Right of Way — unless the opponent exploits the bent arm with a stop-hit. And it gets even more complicated — the fencer can withdraw the hand to invite a stop-hit, and then extend just before the opponent starts their attack (since it’s always easier to change directions of a hand than a whole body).

The opponent knows all this about march footwork — or they will learn it soon enough from the director’s call — and so they perforce have to give ground. The defender is waiting for a footwork opening in Right of Way, and meanwhile trying to create a Right of Way opening with the blade. The blade is one of the defender’s hopes, because any blade noise might be enough to indicate a parry, which allows the defender to take over the action. Consequently, if the attacking fencer can avoid blade contact, he is “protecting” the footwork, which lets the footwork bring the attacker ever closer to the defender.

While the attacker is pressing forward, his hand is making feints to the opponent’s target and derobing around the opponent’s attempts on the blade. The feints and line changes aren’t meant to be pretty, they ought to completely avoid the opponent’s blade at all times. If blade contact is made, priority can shift to the defender, who may then take the offensive.

Should priority shift suddenly like this, it isn’t always disastrous to the march, despite the fact that the now-defender is charging towards the now-attacker. Hopefully, the now-attacker is off-balance and flying backwards, unable to exploit the change in priority. When a parry isn’t followed with a riposte, consideration will shift back to the original attacker with the next threat they make. In effect, an unused parry allows the attacker to continue their marching attack without a stutter.

Ultimately, the march is a house of cards, built on how difficult it is to attack into a preparation which can become an attack at any moment.

Up to this point, the march has been very preparatory. When the time seems right, or the opponent lets the distance get close, or the opponent runs out of strip, the march becomes urgent. This is the phase that most people notice right away — the marcher becomes the attacker for real (not just in spirit). The marcher’s tempo accellerates suddenly, the target is selected, and the committed attack is unleashed.

Are marching attacks difficult to do?

Fencers can spend years in competition and practice getting their marching attacks to work. They’ve been known to spend hours in front of the mirror, practicing footwork and hand combinations, trying to hone a proper balance between arm extending, arm withdrawing (or resetting), footwork, and feints. Often, definitively “safe” combinations are never found by the fencer, and so their marches always have weaknesses that can be exploited by an adroit opponent.

However, marches can be mastered. They are a skill, like anything else. While world-class fencers may be able to improvise, on the fly, an effective combination of footwork and bladework, usually they don’t have to. Fencers can simplify their marches into set patterns, preferred katas, that generally tend to work for them. Study a fencer long enough, and you’ll notice repeats in their hitting actions. A stuttering step, a series of feints — strings of movements that seem idiosyncratic to that fencer, but are actually just derived combinations that were honed Darwin-style based on their success rate, and added to the fencer’s repertoire.

In many cases, good fencers have never investigated the march, or dissected it like we do here. It’s just something they started doing, and then stuck with it because it worked. Doubtless this is how the march evolved in the first place — not as a master’s thesis at Fencing U, but as a street-fighting method in tournaments. Directors and opponents believe the march, because the threat is intuitively obvious.

Next installment: Constructing Safe Marching Attacks.