Before I left for Budapest, I asked the /r/fencing Subreddit what they wanted me to write about. The top response was:

“Stuff that I can steal without doing work or knowing things.”

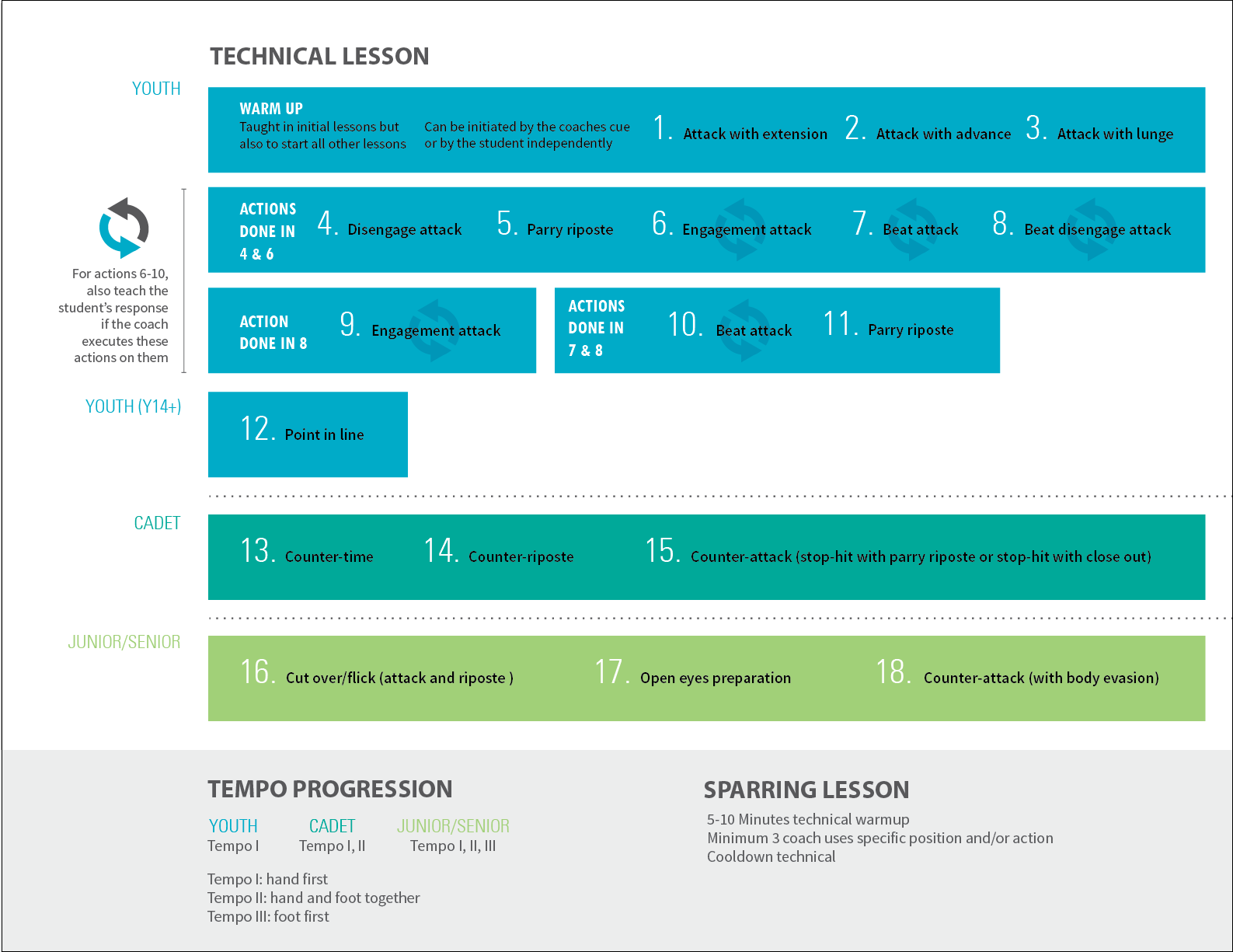

So after a little more than a month of learning the foil system, here’s a short Buzzfeed-style list of five tips for coaches that will make your lessons better if you weren’t already doing these things before.

1. Be closer.

If you’ve watched a significant number of fencing lessons, you’ve probably noticed “coaching footwork.” Giving multiple lessons a night makes doing real fencing footwork (especially lunges) challenging if you want to have a long coaching career. For the lesson to still be effective for the student, the coach needs to be a lot closer to the student that normal fencing distance.

Being closer allows the coach to create real fencing actions/situations despite the lack of footwork.

2. Students should back up before they parry.

Since the coach is so much closer to the student, you can force the student to retreat before they move their hand to parry. The distance will keep students with particularly fast hands from “cheating” correct technical execution. It also allows the student to set up defensive preparations before a final parry.

3. Coaches should back up when students attack.

Part of providing those realistic fencing situations will be reacting like a fencer would. That means backing up when being attacked, and backing up before your parry when teaching the student to disengage. It provides the student with the feeling of successfully landing an attack against an opponent who is doing more than just standing still and letting themselves be hit.

4. Students should not back up for no reason.

If you’ve ever been frustrated with a student who was backing up on the strip while they’re not actually being attacked, it’s likely they learned this during the lesson. If the coach is teaching students to recover and then start retreating in order to reset distance and attack again without an actual threat, that kind of behavior transfers to the strip. Most of the time, the student should only back up when the coach is moving forward or attacking.

5. Actions should be based on reality.

This somewhat violates the “not knowing things” premise, but basing your actions on reality can be done without deep mystic knowledge of the sport — it just requires that you look objectively at how actions are called on the strip and whether or not certain actions are working. Watch your students performing the actions you work on, and reflect on how the referees are making their calls, and/or watch videos of bouts to see how things are called elsewhere.

The example we’ve worked on here has been with point in line. Establishing line typically requires opening the distance, but scoring with line by hoping your opponent just walks onto it is unlikely. While the rules don’t prohibit lunging from line, you can’t rely on referees to make this call reliably. Frequently, lunging even after establishing line will be called a counter-attack. That’s why the system here teaches students to advance to score with their point in line instead.