When most Americans think of swordplay, the images that come to mind are either of the lumbering power of armor-clad knights battling with broadswords, or of the swashbuckling flair of Errol Flynn and other screen duelers of the ’30s and ’40s. In what it requires and how it is conducted, Olympic fencing resembles these two clichés about as much as the Olympic Opening Ceremonies resemble the ritual sacrifice of animals that once signalled the start of competition.

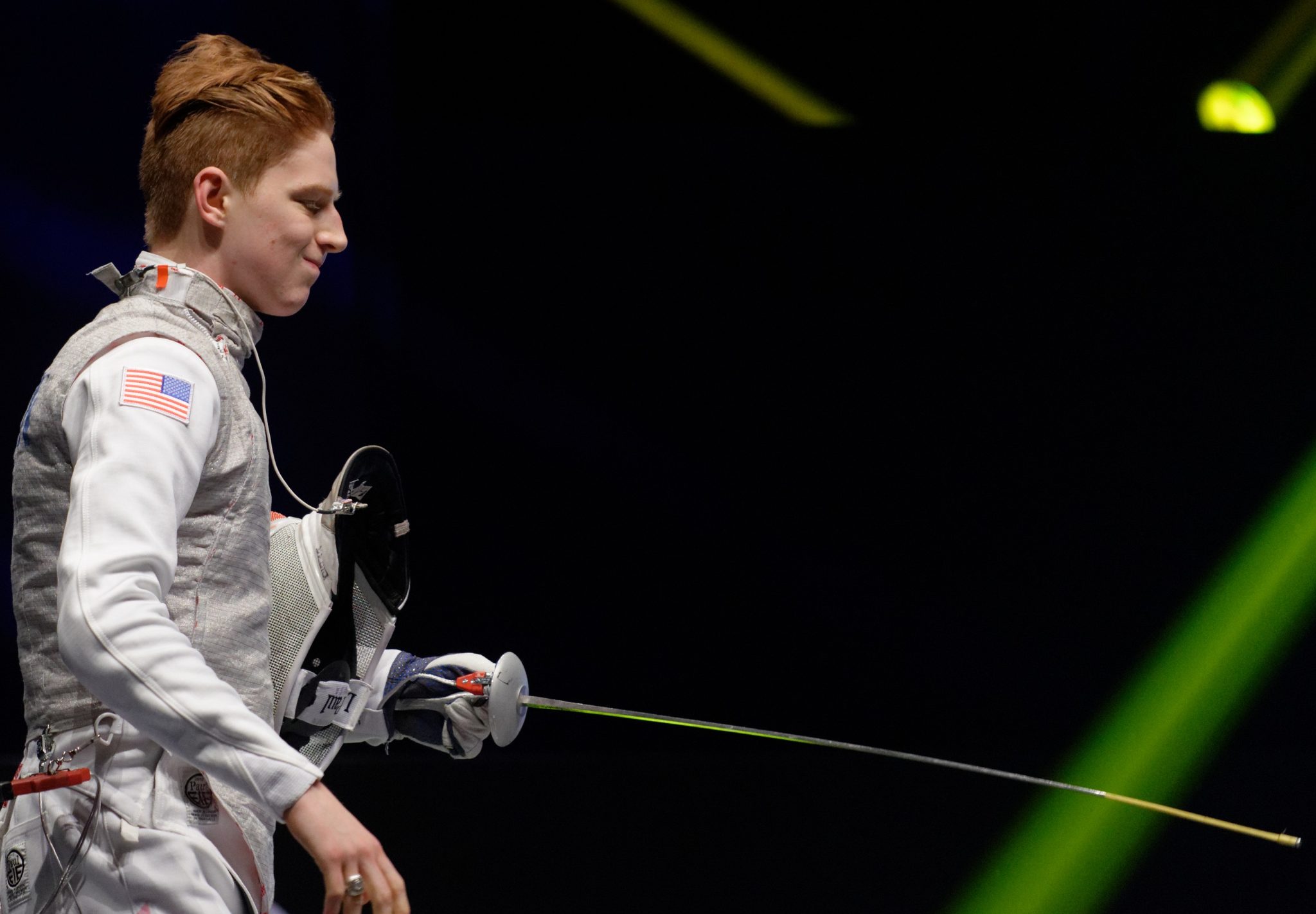

The modern Olympic fencer trains for years, honing agility, quickness, and subtlety of movement. The sport has been described as “chess with muscles,” suggesting that complicated strategy lies behind the thrusts and parries that punctuate a duel. Fencers of today employ a strange combination of archaic and modern customs; combatants still salute before a match and wear the traditional white uniforms and masks, but scoring is now determined by electronic padding worn by the combatants that registers when a hit takes place with flashing, color-coded lights.

As suggested by the continuing power of the myths of swordfighting knights and adventurers, the fencing tradition is rich and storied. Like fellow Olympic sports archery and javelin, fencing has its roots in ancient combat. Around 1200 BC, the Egyptians began the custom of fencing for sport, as seen by images in decorative reliefs from that period depicting knobs on the end of weapons, earflaps and other protective garb. Sword craftsmanship evolved through the ages, from the short, wide swords favored by the Greeks and Romans to the heavy two-handed broadswords in vogue during the age of chivalry. After the advent of gunpowder and firearms, armor became obsolete and lighter swords gained popularity as the sidearm of choice for European officers and gentlemen.

The Italians, Spanish, and French all claim parentage for modern fencing, but throughout Europe during the Renaissance the discipline took on the aura of high art, with masters refining and passing on to a select few their secret techniques. In the 18th century, treatises appeared in print setting forth the current system of rules and scoring, and prescribing the foil, a metal mask with eye slit, and protective jacket or vest as equipment for use. The rules were intended to simulate real combat while protecting the safety of the combatants. “Conventions” were subsequently adopted to limit the target area of the body and providing for a “right of way” for attacks.

Fencing was a clear choice for inclusion in the Olympic program from 1896 onwards. At the time, the sword was still considered an important military weapon, and sword fighting remained a well-established European custom backed by centuries of tradition. In addition to the foil, contested weapons were the epee, descendent of the dueling sword, and the sabre, which evolved from the weapon of choice for cavalry troops. Fencing remains one of just six sports to have appeared in every modern Olympic Games.

In the first decades of competition, Europeans dominated, with France, Italy, Spain, Great Britain, and the Netherlands all boasting champions. Following World War II, the communist nations of eastern Europe rose to pre-eminence, with the Soviet Union, Poland, and Hungary sharing the medal stand. Aladar Gerevich of Hungary is considered fencing’s greatest champion, with seven gold medals in sabre competition to his credit.

| Overview |

(from the 1996 U.S. Fencing Media Guide)

Foil, epee, and sabre are the three weapons used in the sport of fencing. While it is not unusual for fencers to compete in all three events, they generally choose to develop their skills in one weapon. Until recently, women were permitted to compete only in foil, but now the USFA offers national competitions for women in epee and sabre. Women’s epee was added to the World Championships in 1989 and will be held for the first time at the Olympic Games in 1996. Foil and epee are point-thrusting weapons. Sabre is a point-thrusting as well as a cutting weapon. The target areas differ for the three weapons, though all three are scored electronically.

| Object |

The main object of a fencing bout (what an individual “game” is called) is to effectively score 15 points (in direct elimination play) or five points (in preliminary pool play) on your opponent before he scores that number on you. Each time a fencer scores a touch, she receives a point. Direct elimination matches consist of three three-minute periods.

| Foil |

![]()

The foil, the modern version of the dueling rapier, has a flexible rectangular blade, approximately 35 inches in length, weighing less than one pound. Points are scored with the tip of the blade and must land within the torso of the body.

The foil, the modern version of the dueling rapier, has a flexible rectangular blade, approximately 35 inches in length, weighing less than one pound. Points are scored with the tip of the blade and must land within the torso of the body.

The valid target area in foil is the torso, from the shoulder to the groin, front and back. It does not include the arms, neck, head and legs. The foil fencer’s uniform includes a metallic vest (called a lamé) which covers the valid target area, so that a valid touch will register on the scoring machine. A small, spring-loaded tip is attached to the point of the foil and is connected to a wire inside the blade. The fencer wears a body cord inside his uniform which connects the foil to a reel wire, connected to the scoring machine.

There are two scoring lights on the machine. One shows a green light when a fencer is hit, and one shows a red light when her opponent is hit. A touch landing outside the valid target area (that which is not covered by the lamé) is indicated by a white light. These “off target” hits do not count in the scoring, but they do stop the fencing action temporarily.

| Epee |

![]()

The epee (pronounced “EPP-pay”), the descendent of the dueling sword, is similar in length to the foil, but is heavier, weighing approximately 27 ounces, with a larger guard (to protect the hand from a valid hit) and a much stiffer blade. Touches are scored only with the point of the blade. The entire body is the valid target area.

The epee (pronounced “EPP-pay”), the descendent of the dueling sword, is similar in length to the foil, but is heavier, weighing approximately 27 ounces, with a larger guard (to protect the hand from a valid hit) and a much stiffer blade. Touches are scored only with the point of the blade. The entire body is the valid target area.

The epee is also an electrical weapon. The blade is wired with a spring-loaded tip at the end that completes an electrical circuit when it is depressed beyond a pressure of 750 grams. The causes the colored bulb on the scoring machine to light. Because the entire body is a valid target area, the epee fencer’s uniform does not include a lamé. Off-target hits do not register on the machine.

Learn how to fence epee with the CD-ROM series Training of a Champion and Imre Vass’ comprehensive book Epee Fencing: A Complete System.

Learn how to fence epee with the CD-ROM series Training of a Champion and Imre Vass’ comprehensive book Epee Fencing: A Complete System.

| Sabre |

![]()

The sabre is the modern version of the slashing cavalry sword, and is similar in length and weight to the foil. The major difference is that the sabre is a point-thrusting weapon as well as a cutting weapon (use of the blade). The target area is from the bend of the hips (both front and back), to the top of the head, simulating the cavalry rider on a horse. The sabre fencer’s uniform includes a metallic jacket (lamé), which covers the target area to register a valid touch on the scoring machine. The mask is different from foil and epee, with a metallic covering since the head is valid target area.

The sabre is the modern version of the slashing cavalry sword, and is similar in length and weight to the foil. The major difference is that the sabre is a point-thrusting weapon as well as a cutting weapon (use of the blade). The target area is from the bend of the hips (both front and back), to the top of the head, simulating the cavalry rider on a horse. The sabre fencer’s uniform includes a metallic jacket (lamé), which covers the target area to register a valid touch on the scoring machine. The mask is different from foil and epee, with a metallic covering since the head is valid target area.

Just as in foil, there are two scoring lights on the machine. One shows a green light when a fencer is hit, and one shows a red light when the opponent is hit. Off-target hits do not register on the machine.

Right of Way

One of the most difficult concepts to visualize in foil and sabre fencing is the rule of right-of-way. This rule was established to eliminate apparently simultaneous attacks by two fencers.

In essence, right-of-way is the differentiation of offense and defense, made by the referee. The difference is important only when both the red and green lights go on at the same time in foil and sabre. When this happens, the winner of the point is the one who the referee determined was on offense at the time the lights went on.

Epee does not use the right-of-way in keeping with its dueling origin – he who first gains the touch earns the point. Or, if both fencers hit within 1/25th of a second of each other, both earn a point. However, it is equally important to have a sound defense for epee, since the entire body must be protected from a touch.