“As I look back on my fencing career and the millions of dollars I was able to earn from it, I’m overjoyed that our sport presents so many opportunities for us to thrive as professional athletes and gain oodles of money. Wait, be right back. Nike’s calling me. I think they want to renew my endorsement deal.”

-No One. Ever.

“Amateurism can never succeed in a society which has egalitarian beliefs. It may be that amateur athletics at a high level of expertise can only exist in a society dominated by upper class elitists.”

-Ronald Smith

Prior to the prestigious 1920 Henley Regatta, American rower John B. Kelly applied to enter the race and was subsequently rejected. Although Kelly had an impressive rowing résumé that included six U.S. National Championships and three Olympic Golds, the rationale for refusing him entry was simple: he was a bricklayer.

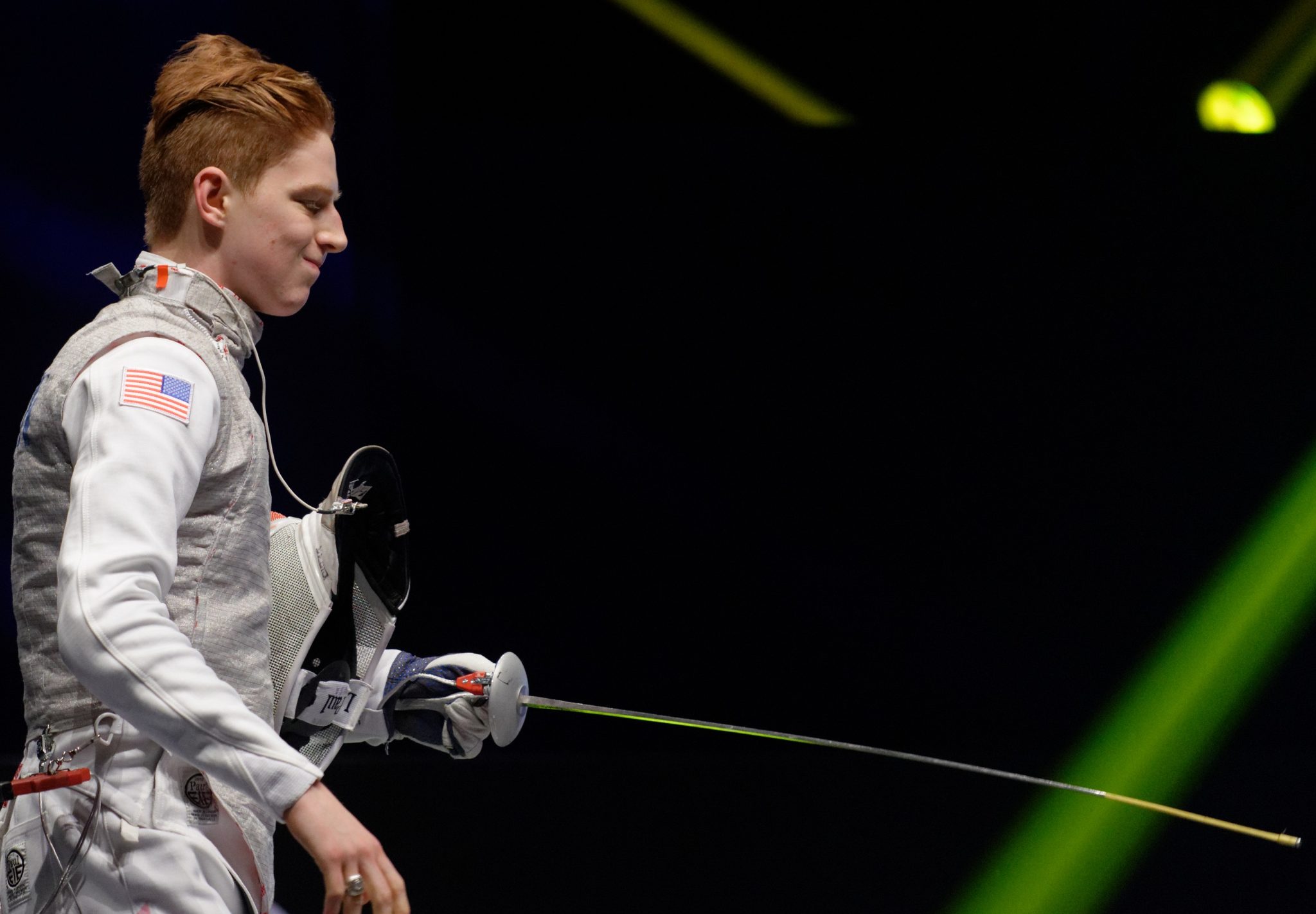

Nearly 100 years later, the stringent and absolutist values of amateurism have since (gradually) loosened, but as Race Imboden’s article “Foiled” points out, many of the elitist and patrician principles of amateurism continue to permeate both fencing and sporting culture as a whole.

From its origins in Victorian England, amateurism served the purpose to further the chasm between upper and lower classes and to promote the idea of “sport for its own sake,” a task that was reserved for the rich and wealthy. At the turn of the 20th century, Baron Pierre de Coubertin established the modern Olympic Games while his friend, President Theodore Roosevelt founded the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (IAAUS), the predecessor to the NCAA.

Both the Modern Olympic Games and the IAAUS espoused the values of amateurism, but as organized sports rapidly grew in both participation and popularity, the egalitarian social values of United States culture would begin to define American sport, while the governing bodies continued to promote an aristocratic system, creating an ideological clash that is becoming increasingly apparent in the 21st century.

Through the eyes of de Coubertin, amateurism was never intended to be commercialized and profited from; yet, as the NCAA now brings in close to $1B in annual revenue and $500M through TV deals[1], amateurism profits while amateurs are forced to abide by an archaic value system.

While Fencing is mostly immune to the larger scale duplicity seen in collegiate football and basketball, there are a sufficient number of asinine and antiquated rules that continue to affect the sport. In “Foiled,” Imboden begins to graze the surface of the hypocrisy and elitism that remains in contemporary America.

Like many Americans, Imboden’s father lost his job in the midst of the Great Recession. As Imboden’s fencing career was beginning to flourish, he was forced to fund his passions through modeling, a talent that ultimately (and ironically) cost him his NCAA amateur status.

Just as John B. Kelly was denied entry into the 1920 Henley Regatta for holding a job, Imboden was presented with a similar quandary: model or fence. Due to his financial circumstances, fencing could not exist without modeling; thus, he was needlessly forced by the NCAA into sacrificing his eligibility, a victim of Victorian values in the present day.

The irony in Imboden’s tale is just how little profit or individual gain there is to be had in the sport of fencing. In contrast to the cash cow that is NCAA Football, Division I Fencing programs lost a combined $330K in 2013 alone[2]. Attempts to professionalize fencing have resulted in utter failure, as the sport is deeply rooted in amateurism—a fact that is often lost in the NCAA’s hammers to athletes like Race.

Commiserating about fencing related debt among Olympic athletes is commonplace, and with no trajectory into a professional league, the line between “professional fencer” and “amateur” is a thin one. And yet, with his father unemployed and a desire to fund his own fencing, the NCAA still poured salt on the Imboden family’s wound while reaping the fruits of amateur athletes’ labor to the tune of a billion dollars.

If amateur values are supposed to promote “sport for the sake of sport,” then those principles backfire in Fencing. Fencers who compete at the collegiate level are barred from representing their USA Fencing club in competition; athletes will soon be banned from having a “USA” stencil on their uniforms, and even wearing a club’s patch while in NCAA competition is a violation of their frivolous little rules, because it amounts to advertising, in the same way that downing a Big Mac and a milkshake equates to dieting; that is to say, not at all. An insistence to enforce these rules blocks the forest through the trees and undermines the simple reason why we fence: for the sake of fencing.

Everyone wins when Race Imboden models with his shirt off, but a shirtless Race and a fencing Race shouldn’t have to be mutually exclusive. While admirable in many of its ideals, amateurism is a little bit like going to happy hour with O.J. Simpson: decades ago, it might have been cool, but now, you want to run in the opposite direction. As collegiate athletes begin to unionize and set the table for a legal battle with the hypocritical NCAA, the fight ahead not only stands to redefine amateurism as we know it, but to expunge the elitist, Victorian values that have remained in sport for so long. Those values denied John B. Kelly of his desire to row, of Race Imboden his ambitions to fence, and of Jim Thorpe his Olympic gold medals. To amateurism and the NCAA, it’s time to wave our hands and say: “Hasta la vista.”

[1] http://www.sportingnews.com/ncaa-football/story/2012-11-21/college-football-playoff-espn-tv-rights-12-years-500-million-bcs

[2] http://www.ncaapublications.com/productdownloads/D1REVEXP2013.pdf